A tired psychiatrist sits with his patient on the steps of a red-brick asylum. Birds chirp merrily in the sunlit garden. A few inmates, scattered across the lawn, tend to the bushes while some others stare blankly into space, windswept hair clinging to their heads at odd angles. At the end of a short, poignant conversation, the well-dressed patient looks at his friend and asks,

“Which would be worse…to live as a monster, or to die as a good man?”

Leaving the weight of this profound line to sink in, he stands up and walks slowly down the steps towards two white-robed attendants. Flanked by his silent companions, the patient shuffles away into the distance as ominous music plays in the background.

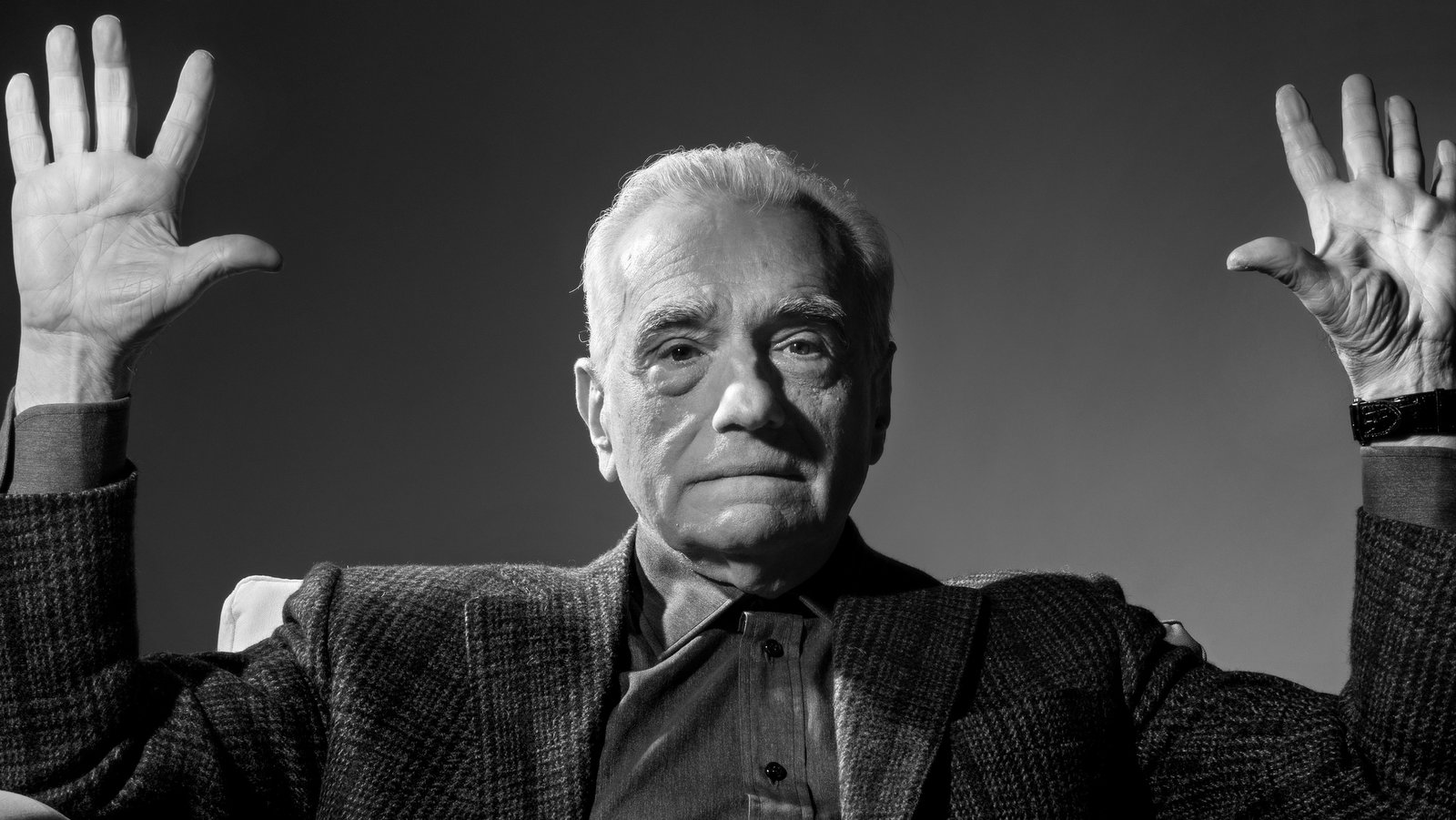

This is the ending scene of Shutter Island, a film that befuddles as much as it delights, as it leads its audience on a bizarre trip through the rich imagination of Martin Charles Scorsese, the world’s most influential film director.

Born in New York City in the midst of the Second World War, Scorsese was the son of two garment workers of Italian descent. As an asthmatic little boy growing up in Manhattan’s Little Italy, sports and other outdoor activities were beyond his range of exertion. Fate often has the strange habit of using our weaknesses to tap into our deepest potential, and so it happened that the housebound Scorsese found his solace in movie theatres, where his parents and older brother often took him to. In a stirring article in the New York Times, the director recounts how he, eighteen years old at the time, saw Alfred Hitchcock’s legendary thriller Psycho at a midnight show on its opening day, calling it “an experience I will never forget”. It is unsurprising how this youthful pastime translated into a lifelong love for storytelling on the big screen.

Graduating from high school in 1960, the young Scorsese initially desired to become a priest, and attended a preparatory seminary but failed after the first year. This led him to enroll in NYU’s Washington Square College, where he earned a BA in English and later a Master of Fine Arts degree. His religious inclinations never left him however, as he revealed in a 2016 interview, “After many years of thinking about other things, dabbling here and there, I am most comfortable as a Catholic”. Catholicism played an influential role in his filmmaking, made evident from the iconic Cross tattoo on the back of villain Max Cady in Cape Fear, the religious connotations of The Last Temptation of Christ, and the numerous church scenes in Mean Streets.

Starting with short films such as What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This?, Scorsese’s talents and career blossomed in the 70s and 80s with Taxi Driver – the tale of a surreal escapade in the life of a war veteran named Travis Bickle – winning four Oscar nominations including Best Picture, propelling him to international stardom. Like Brian De Palma, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg, the famed “movie brats” of the 70s, Scorsese developed a unique style of filmmaking over the years with his trademark approaches and thematic choices making his films some of the best the world has ever seen.

All films are, in essence, stories told in the medium of sight and sound. The plot of the story underpins every scene, motivates the decisions of every character, and leaves a unique imprint on the mind of every viewer. If the frames of the movie were water, the plot would be the glass holding the water; it is the form of the glass that we often notice the most. Scorsese’s glasses come in peculiar shapes but are always well finished; none of his films can be called vague or experimental. This is quite unlike some directors (David Lynch in particular) who create movies that are intentionally murky in the logic that connects the individual scenes. When the final frame of Shutter Island flashes on the screen, we know we have been cleverly duped, but we never question the coherence of the story; the clues were there all along, if only we had been sharp enough to pick them up.

At first glance, the variety of Scorsese’s storylines is striking. From the machete-wielding 19th century gangster Bill the Butcher in Gangs of New York to the little boy mending clocks in a Parisian railway station in Hugo, we meet a wide range of characters across a multitude of settings. However, many of them share similar story arcs and the films themselves have several recurring themes.

Violence is almost a staple theme in Scorsese’s movies. Casino contains brutality to the extent of a slasher horror movie, with an ending scene where some characters are mercilessly beaten to death with clubs and then buried. Taxi Driver and Goodfellas are replete with bloody gunfights taking place in the sleazy suburbs of New York. Often considered a master of the “gangster movie”, his work ranges from Mean Streets in 1973, which tells the story of a young man indebted to the mob, to The Irishman in 2019, about a hitman who “paints houses” with the blood of his targets, justify this characterization. Many commentators, including Scorsese himself, cite his childhood in the Little Italy of the 50s as a clear influence on this choice of theme. The director recounts how he used to watch from his bedroom window as local mobsters drove up in flashy cars, double-parked in front of fire hydrants, and how no cop ever dared to write them a ticket. Fittingly, in a nod to the director’s roots, the protagonist of Goodfellas echoes that “As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.” Notably however, despite giving his often sadistic characters their share of cinematic glamour, Scorsese never glorified violence, showing it to never provide the catharsis they desired.

Going hand in hand with the recurring theme of violence is the director’s ensemble of deeply flawed and self-destructive characters. In Raging Bull, a semi-biographical account of the life of boxer Jake LaMotta, we meet the protagonist (acted by long-time collaborator Robert De Niro), whose incessant rage, while proving to be devastatingly effective in the ring, alienates him from his family. As his life falls apart before him, he routinely breaks down the doors of his own house and once ends up beating his head and fists on a wall in a shockingly comical fit of anger. The well-known Wolf of Wall Street features a protagonist (acted by Leonardo DiCaprio of Titanic fame) who is self-destructive in a less obvious way. This is a tale of rampant capitalism, in which the protagonist ends up unravelling his hedonistic empire when he can’t stop himself from wanting more. Wolf of Wall Street’s wild excesses does not fail to spill over into its dialogue, which holds the record for the most number of f-words ever used in a single film, with its count of 506 uses boiling down to an astonishing rate of around one f-word every twenty seconds!

Women hold a queer position in Scorsese’s movies. Despite only usually appearing as supporting roles to the central male character, his female leads are commanding, independent figures, who play a pivotal part in the transformation of his flawed hero. Strikingly, his leading ladies are often blonde, are dressed in white when they first appear in the film and unsurprisingly, portray the love interest of the protagonist. The choice of hair color could be a tribute to the iconic blonde in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, one of Scorsese’s favorite films, while the choice of dress color is symbolic of how the protagonist sees the woman as angelic, representing a divine ideal beyond the gritty realism of his existence. This perception is enhanced by the director choosing to show the first appearance of the leading lady in slow motion as if to suggest that the world slows down for the protagonist when he first sees her. However, his protagonists usually discover through the course of the film that women are not exempt from the imperfections of reality and do not fit cleanly into their stereotypical standards. “Didn’t you ever hear of women’s lib?” asks Iris in Taxi Driver. Scorsese clearly has. Poor Travis Bickle unfortunately, has not.

America is often called the “land of opportunity”. Scorsese’s movies explore the merits of this title, usually highlighting the darkness underlying its fabled system of justice and democracy. Political corruption and its partnership with crime feature in many of his films, from the bent cop who looks the other way when handed a fiver in Mean Streets to the high-level corruption depicted in The Irishman. “America was born in the streets” declares a slogan of Gangs of New York, and is apparently yet to wash off the grime.

Artists excel at tuning in to the trends and sociopolitical undercurrents that course through communities; it is precisely the addressing of these issues that moves audiences to empathize with their work, transforming artists into popular artists. Scorsese, arguably the most popular director of all time, is no exception to the rule. Ever the perspicacious observer of American culture, Scorsese anticipated the rise of the reality show in The King of Comedy, a dark comedy starring Robert De Niro as an unsuccessful comedian seeking the spotlight. In the words of Professor Marc Lapadula, lecturer in film studies at Yale University, “The King of Comedy is a movie about this idea of obsession with fame in America, and the obsession to be famous even if you don’t have a talent.” Notably, The King of Comedy was released long before Keeping Up with the Kardashians was even thought of. Many of Scorsese’s other films too have a uniquely American feel to them. Taxi Driver, Bringing Out the Dead, Mean Streets, After Hours, and Raging Bull are all set in contemporary New York while The Age of Innocence and Gangs of New York are also set in the same city, albeit in different periods of history.

Having grown up on movies, many of Scorsese’s own works contain subtle tributes to the films that awed and guided him on his journey to greatness. In The Departed, scenes of death and murder are often prefaced by frames containing a surreptitious ‘X’ in the background. This is Scorsese tipping his hat to a similar technique used in Scarface, a film released in 1932 which set the tone for the future of the ‘gangster’ genre. Another scene from The Departed depicts one of the main characters taking a shower. The editing of the scene, including a close-up of the shower filter, is reminiscent of a jarring scene in Psycho, the movie that so impressed Scorsese as a teenager. Raging Bull, one of his most critically acclaimed films, is dedicated to his college mentor Haig P. Manoogian, to whom Scorsese pays tribute in the end credits by quoting biblically, “All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see.”

In 1895, the Lumiere Brothers screened one of the world’s first-ever movies, a 1-minute affair starring a train arriving at a station. To the audiences of the time, this was nothing short of a thrilling experience, with some of them jumping out of their seats in alarm as the locomotive rushed towards them on the screen. This comic but fleetingly nostalgic scene appears in Scorsese’s Hugo, along with many other events from the early days of cinema. The director’s passion for cinema history and its preservation extends beyond the big screen, as seen from his ventures such as The Film Foundation, The World Cinema Project, and The African Film Heritage Project.

Every film we see takes us into a unique little world whose creator is the film’s director. Unburdened by the laws that govern the real world, the director finds himself armed with a powerful cinematic paintbrush, whose strokes can fashion every detail the audience perceives about the world of the film. This is a double-edged power however, and directors who use it too liberally (Bollywood comes to mind) find their films the subject of much ridicule. Maestros like Scorsese therefore, go about the business of world-building in very meticulous ways.

One significant world-building technique in many of Scorsese’s movies is the use of narration and montage. Montage is a film editing technique in which a series of short shots are sequenced to condense space, time, and information. Often supplied with a fitting soundtrack, montages help to summarize events taking place over a long time or to prepare a particular setting in a movie. For example, in Taxi Driver, a series of suggestive shots that occupies less than two minutes of the film takes the audience through the streets of New York, with the cheap nightclubs, preoccupied people, and dim lights setting the tone for the story to follow. A narrative monologue adds to the effect, with Travis Bickle’s dismal, pessimistic take on urban life helping the audience to absorb the psyche of the main character. A legendary line improvised by Robert De Niro epitomizes Travis Bickle’s monologues; he stands alone in a room and whips out a handgun, points it at a mirror, and with a smug expression on his face, challenges his reflection with “You talkin’ to me?”

The cinematography of Scorsese’s films places the audience in the shoes of a silent participant in every scene, as opposed to limiting their role to that of a static observer. The camera often seems to have a life of its own; it engages in all the action. In Raging Bull, we are placed in the middle of a boxing match where punches that land, make the camera swing wildly as if it received the blow and in The Wolf of Wall Street, the crowded workplace of the main character is shown in 360-degree shots with the camera swiveling around to capture the celebrations of success. The camerawork also echoes the psychological space of the main character; when LaMotta is on the verge of a victory in Raging Bull the boxing ring appears smaller, signifying his dominance of the ring, while when he is boxed onto the ropes, the ring appears larger as the camera moves downwards, showing his opponent looming over him.

Scorsese is also well known for his use of long takes. A long take is a shot (a series of frames that runs for an uninterrupted period of time) with a duration much longer than the conventional editing pace either of the film itself or of films in general. The so-called “Copacabana shot” in Goodfellas lasts for around three minutes as it follows the main character who takes his girlfriend through the back door of a nightclub. The uninterrupted shot shows the main character interacting with everyone from the waiter to the manager as he impresses the girl and the audience with his power and influence. Similar long takes are also seen in Casino and The Age of Innocence. Freeze frame, the technique of pausing the flow of the film to hold a single frame for several seconds on the screen, is used in Casino, The Wolf of Wall Street, Goodfellas, and Raging Bull to halt and emphasize critical moments in the story.

Rock music is a usual companion of almost every montage in Scorsese’s films. Gimme Shelter, by The Rolling Stones, features in no less than three of Scorsese’s movies: Goodfellas, Casino, and The Departed. The director uses music in key moments of a film, often in scenes of love or violence to accentuate the effect of the scene. Loud guitar strumming fades away all diegetic noise (sounds that emanate from the story-world of the film) and lends the scene a surreal, eternal form. For example, when the main character of Casino meets his love interest in the middle of a noisy game of poker, the screen freezes for a moment, and with the leading lady’s sparkly smile on screen, the chatter of the casino bursts into a rendition of Love is Strange by Mickey and Sylvia. Sounds cheesy, but Scorsese pulls it off in real style.

Today, the 79-year-old Martin Scorsese is busy at work on his next film, Killers of the Flower Moon, due to be released in 2022. On a final note, movies are meant to be watched – not read about. We live in the Age of the Internet, and to you, Scorsese’s marvelous universe with its stories, characters, and joys, is just a few clicks away. So just press the download button, make yourself comfortable and step into the world that beckons. Happy watching!

Image Credits:-

- Featured Image: https://bit.ly/3fsb8mu

- Content Image 1: https://bit.ly/3rEx17Z

- Content Image 2: https://bit.ly/33gcs9J

- Content Image 3: https://bit.ly/3Kp6ELM

- Content Image 4: https://bit.ly/33mtRNR

- Content Image 5: https://bit.ly/33FuaD2

- Content Image 6: https://bit.ly/3KaHJLI